Why the greatest gift a master can give is a punch to the face.

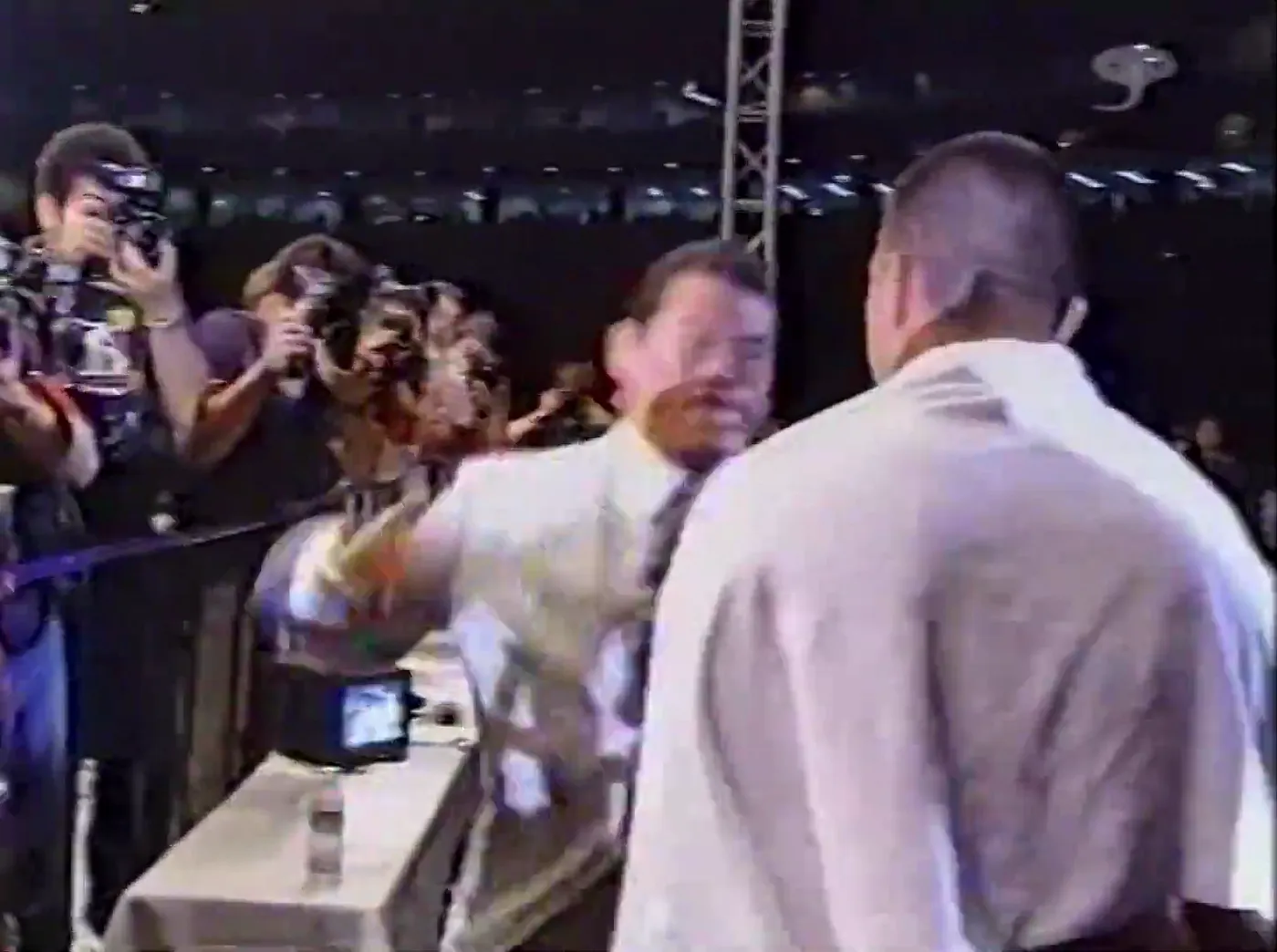

May 2, 2003. The Tokyo Dome. Fifty thousand people.

A 25-year-old named Lyoto Machida has just done the impossible. He’s brought traditional Shotokan karate into a cage fight — something the smart money said would get you killed — and won.

His brain is flooded with dopamine, endorphins, adrenaline. He feels like a god.

So he walks into the crowd to pay respects to Antonio Inoki — the man who fought Muhammad Ali in 1976, founded New Japan Pro Wrestling, served in Japan’s parliament. To a young fighter, Inoki isn’t just a boss. He’s the sun around which the entire combat sports world orbits.

Machida approaches. He bows deeply.

Inoki steps into his personal space. Places a fist gently on Machida’s chest. And slaps him. Full-torque, open-palm strike to the face.

He slaps him again.

Then he closes his fist and punches him. A full punch to the jaw of a man who just won the biggest fight of his life.

Transport this to Las Vegas. Dana White decks a newly crowned champion. Police called. Lawsuits filed. Internet melts down.

But Machida didn’t flinch. He took the blows, absorbed them, and bowed again.

Years later, reflecting on this moment, he said: “Every Japanese guy wanted to be slapped by Antonio Inoki. Maybe because of that, I had success in my career.”

Then he dropped the line that anchors everything:

I wish he had hit me more.

What do we do with that?

Why does a winner, in their moment of absolute triumph, crave pain?

The Violence That Heals

This ritual has a name: the Toukon Binta — the “Fighting Spirit Slap.”

It started in the 1980s when a cocky student at Waseda University punched Inoki during a talk. Inoki slapped him to the ground. The student stood up, bowed deeply, and shouted: “Thank you!”

He later passed his entrance exams. He told everyone the slap had “woken him up.”

Inoki slapped over 20,000 people in his lifetime. Fighters, politicians, celebrities, students before exams. On New Year’s Eve 2000, he slapped 108 people in a row — one for each earthly temptation in Buddhist tradition.

People didn’t tolerate it. They requested it. They lined up for hours.

There’s a concept in anthropology called mimetic magic — contact with a powerful entity transfers power. The pain was merely the copper wire conducting the electricity.

Think about that. The sting when someone criticizes your work. The discomfort when a mentor says your pitch isn’t ready.

What if that discomfort isn’t damage? What if it’s electricity?

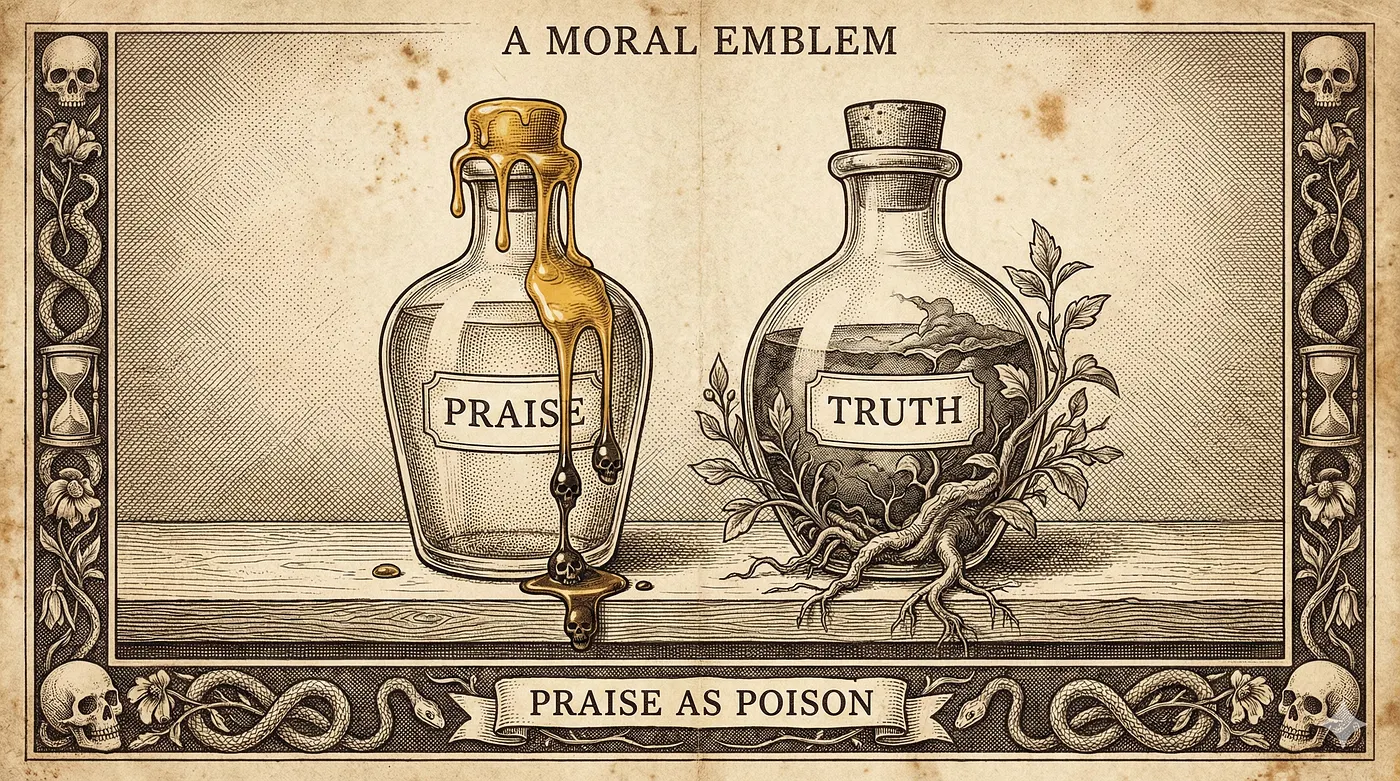

Praise at the wrong time can be poison.

The Forge Behind the Dragon

To understand why Machida could receive those blows with grace, you have to understand who forged him.

His father, Yoshizo Machida, was a seventh-degree Shotokan master. Training began at 5:30 AM. Every day. For thirty years.

But physical training was only the visible part. Yoshizo was relentless about something harder to measure: humility.

“The minute you stop being humble,” he told Lyoto, “is the minute you stop moving forward as a fighter and a person.”

After every fight Lyoto won, his father reminded him: “He should leave the ring being more humble than when he walked in.”

Lyoto described it: “For him, it’s never good enough, which is great for me because I always want to get better.”

His father never said “good job.” Never said “you’ve made it.” Never let him rest on a victory.

And Lyoto is grateful.

Here’s what Yoshizo understood: Praise at the wrong moment is poison.

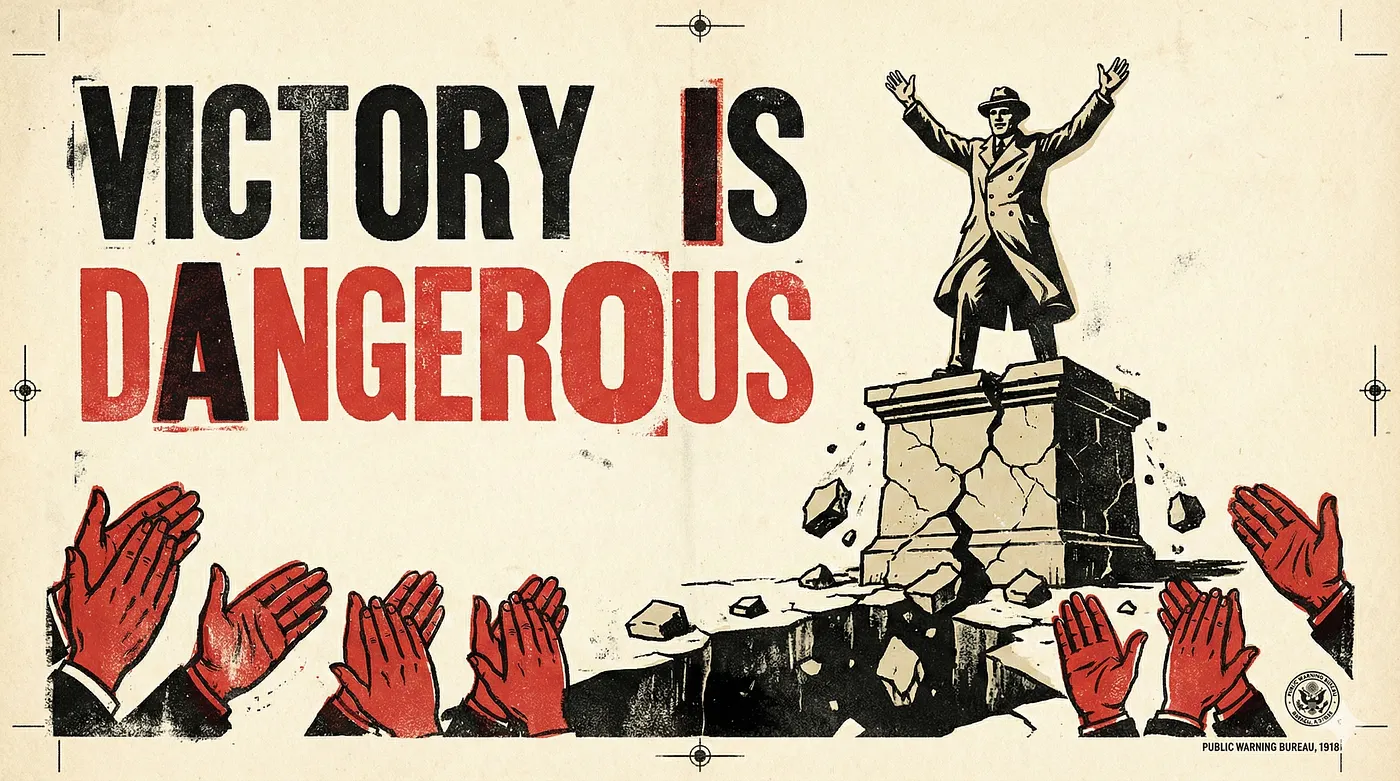

The instant after victory is the most dangerous time in any warrior’s life. Dopamine floods the brain. The ego inflates. The mind whispers: “You did it. You’re special. You can relax now.”

That whisper has killed more careers than any opponent ever could.

The samurai called it zanshin — “remaining mind” — staying alert after victory, because that’s when you’re most vulnerable.

Yoshizo wasn’t being cruel. He was cutting out ego before it could metastasize.

The Evidence

From 2003 to 2009, Machida went undefeated. He became UFC Light Heavyweight Champion.

According to FightMetric, he absorbed fewer strikes than almost any fighter in UFC history — only 0.6 per minute. Less than one strike every two minutes.

He was untouchable.

The man who got hit the least in his professional life was the one who craved the hit from his master the most.

That’s not coincidence. That’s causation.

He accepted painful correction in controlled environments — backstage, in the dojo, at home — so he wouldn’t have to accept it from an opponent’s fist.

He outsourced the pain. He paid in humility so he wouldn’t pay in unconsciousness.

Victory is dangerous if you stop and rest at your peak, because there is no rule that says you ever have to peak.

The Correction You’re Not Getting

When was the last time someone you respect told you that you were wrong?

Not a troll. Not a competitor. Someone who actually cares about you — who told you the truth when the truth hurt.

If you can’t remember, you’re in the danger zone.

We surround ourselves with people who validate our excuses. We curate feeds that show us only agreement. We build echo chambers and call them communities.

Victory is the most dangerous moment.

When you win, your defenses drop. Your ego inflates. You become blind to your own weaknesses.

The slap is a rescue mission — pulling someone out of a burning building, except the building is their own ego and the fire is their success.

You don’t have Antonio Inoki. Neither do I.

So immediately after a win, before the dopamine lies to you, ask:

- Where did I get lucky?

- What almost went wrong?

- What would I do differently?

But here’s the harder truth: the self-administered slap probably isn’t enough.

The ego is a brilliant lawyer. It will always spin the narrative so you’re still the hero.

Lyoto Machida had discipline most of us can’t fathom. And he still needed Inoki to hit him. He craved it.

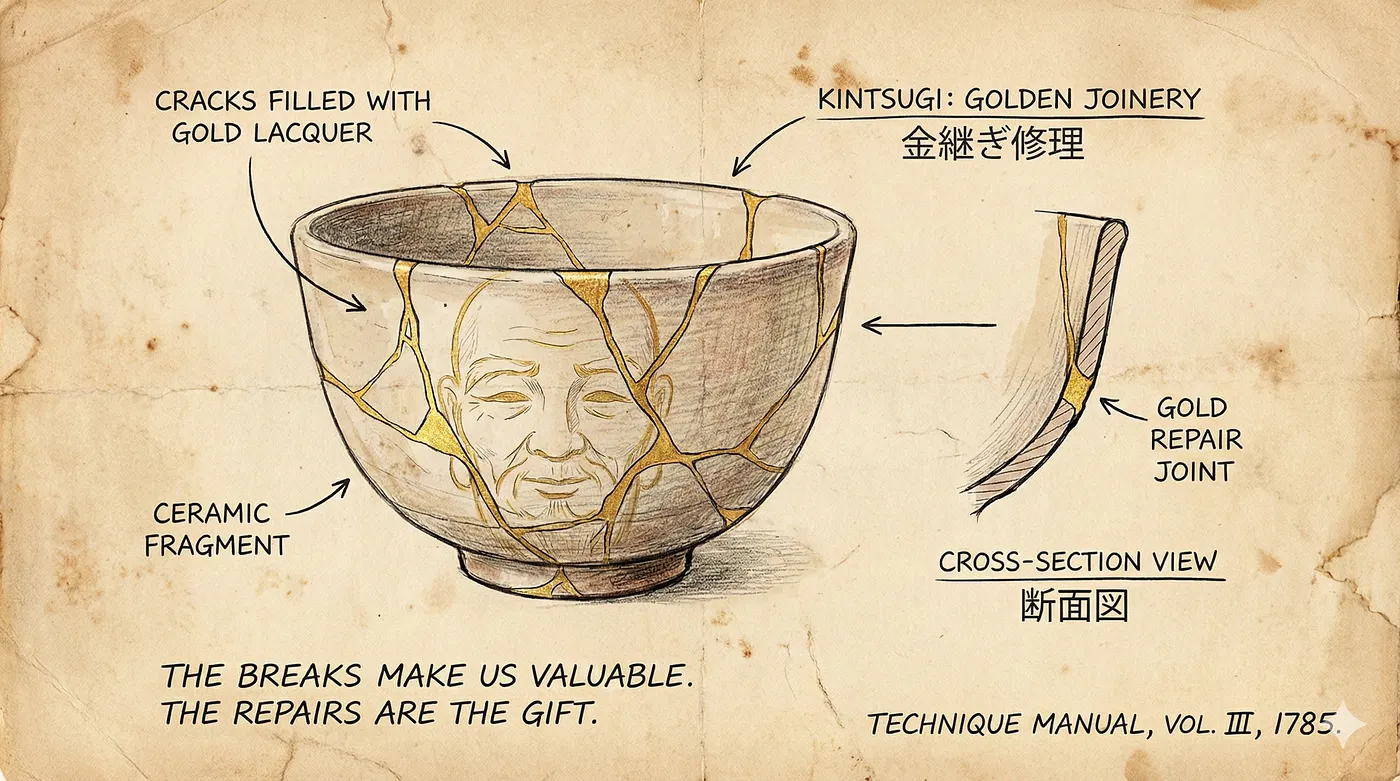

The body remembers what words cannot encode.

Who strikes you when you win?

Not who celebrates with you. Not who validates your success.

Who cares enough to keep you sharp? Who loves you enough to prevent the ego that’s forming?

The mentors who change your life are rarely the ones who make you feel good. They’re the ones who make you feel seen — including the parts you’re hiding from.

If you don’t have that person, you’re flying blind. Your decline has likely already started.

You just don’t feel the descent yet.

Antonio Inoki died on October 1, 2022. There will be no more slaps.

But the question remains:

Go find your Inoki. Find the person who loves you enough to tell you the truth when the truth hurts.

Lyoto Machida absorbed fewer strikes than almost any fighter in history. But the strikes that mattered most weren’t the ones he blocked.

They were the ones he received — willingly, gratefully — from the masters who loved him enough to keep him humble.

The victory is yours.

Don’t let it destroy you.

Own Your Stupid. Rewrite Your Story.

FAQ

What is the Toukon Binta (Fighting Spirit Slap)?

Toukon Binta is a ritual popularized by Antonio Inoki where a “wake up” strike symbolizes intensity, discipline, and psychological calibration. In this story it isn’t random violence—it’s a targeted interruption of ego at the most dangerous moment: right after a win.

Why would Lyoto Machida want to be hit after winning?

Because winning is intoxicating. Dopamine and praise inflate identity fast, and identity makes people sloppy. Machida wanted correction that kept him honest—grounding him in reality before success turned into comfort.

What does “victory is dangerous” mean?

Victory lowers your defenses. You stop scanning for weaknesses, you stop iterating, and you start believing your own story. “Victory is dangerous” means the moment you feel safest is often the moment you begin drifting toward decline.

How does this connect to “Own Your Stupid”?

Own Your Stupid means staying teachable—especially when you’re winning. The point isn’t self-criticism; it’s refusing the ego’s illusion of completion. You don’t “arrive.” You keep earning it.

Is praise bad, or is it just badly timed?

Praise isn’t the enemy—timing is. Praise right after a win can become a sedative: just enough comfort to pause the habits that made you dangerous. Better praise rewards process, not identity.

What’s a modern version of the “Fighting Spirit Slap” in business?

It’s honest feedback from someone competent, delivered while you’re still celebrating. A mentor who points out what’s weak while everyone else is clapping. A teammate who challenges your blind spots before the market does.

How do I find “my Inoki”?

Look for three traits: competence (they’re right), courage (they’ll say it), and care (they’re doing it for your growth). Then make it explicit: ask them to correct you after wins, not just after losses.

Why isn’t self-reflection enough?

Because the ego is a brilliant lawyer. It can argue luck into destiny and mistakes into “style.” Self-reflection matters, but outside correction keeps the story honest and the standards real.

What questions should I ask myself right after a win?

Use a post-win audit: Where did I get lucky? What almost went wrong? What did I avoid noticing? What would embarrass me if it happened again? What would I do differently if I had to repeat this tomorrow?

Is discomfort always a sign something is wrong?

No. Discomfort can be friction from growth, not damage from harm. Sometimes the sting is information. Sometimes the discomfort is electricity—energy that can refine you if you don’t flinch.

What does “Protect the Signal” mean after a win?

Wins bring noise: praise, attention, dopamine, identity inflation. Protecting the signal means staying connected to the truth and process that produced the win—before applause rewrites your standards.

How can leaders apply this without becoming harsh?

Correction isn’t cruelty. The Stupid Movement version is high standards + high care: be specific, actionable, and clean in delivery. Don’t humiliate—calibrate. Don’t punish—refine.

What’s the difference between constructive correction and destructive criticism?

Constructive correction is specific, actionable, and anchored to growth. Destructive criticism is vague, personal, and designed to reduce you. One builds skill. The other builds shame.

Why do top performers seek harder feedback?

Because they worship accuracy, not comfort. They’d rather feel the sting early than pay later. They treat feedback like a training partner: uncomfortable sometimes, protective long-term.

What’s the core message of the article in one sentence?

The win isn’t the finish line—it’s the moment you need truth the most.